Charity Adams was already on her way to the European theater in January 1945, and there was a sealed envelope on her lap. It was time to find out where she was going. She tore open the sealed orders and gasped. It was the job every officer coveted: command, troop time, and being in charge. Adams, who had been the highest-ranking Black officer at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, had commanded a training company, which was a good experience, but to be selected to command a battalion—a brand-new unit—overseas during wartime was a tremendous vote of confidence in her abilities. It was every opportunity she could have hoped for.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Adams had been born in 1919, at a time when the U.S. was celebrating victory in World War I. The next year, the 19th Amendment was passed, and women were given the right to vote. It was a time of change in the country. A feeling of optimism was in the air, and it felt like new possibilities were open for women—unless you were Black. Then it was still a fight, all the way. Growing up in Columbia, S.C., the oldest of four children of a minister and a teacher, she’d been first in many things in her life, including being first in her high school class, valedictorian, and she continued that streak in 1942, becoming part of the first officer class of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC, later simply WAC).

By the time she reached Fort Des Moines for basic officer training, she’d already gotten her first taste of racism in the Army. A white lieutenant had insisted and made certain that Black recruits didn’t sit with the white women on the bus headed for the camp. In that first officer class, there were 400 white women. There were also 40 Black women—the “ten percenters.” While their training was integrated, their living conditions were not.

The Army had scrambled to assemble Adams’ new unit, the 6888th Central Postal Battalion. By 1944, there was a two-year backlog of mail for troops, members of the Red Cross and civilians serving in Europe. There simply weren’t enough postal units. The all-Black WAC unit, known as the “Six Triple Eight,” was the only Black WAC unit to be deployed—another first, with an impossible mission.

The Six Triple Eight’s 855 women were sent to Birmingham, England. When the first contingent arrived, Adams was there to meet their ship. Many had been seasick on the trip over. After being chased by submarines, others were glad to be on land. Their arrival came with a message about the danger of their work—a German V1 rocket, the “Buzz Bomb,” came screaming in just as the women were heading down the ramp. They ran for cover as it hit the dock close to where they were disembarking. No one was injured, but it was a definite reminder that they had arrived in a war zone.

It was the first time some of the young women were away from home. They’d been sick at sea for months, bombed, and now had to work in a strange new country. The troops moved into accommodations within a former school building and marched to their work location the next day. It was cold and dreary outside, and the dark warehouse in front of them that would serve as their workspace was unheated. The windows were blacked out for safety from air raids. Reluctantly, the women filed inside to see their new place of business.

They’d all heard the rumors—there were millions of pieces of mail piled up in the dingy, overcrowded warehouse. It turned out the rumors were true: a mess of monumental proportions was just lying there in the dark waiting for them. A few of the women shrieked when they saw rat eyes glaring at them in the semidarkness. They could hear other rats racing away into the gloom, climbing the swaying towers of mail bags. Other women curled their lips at the smell of mold, spoiling food and the sight of torn packages leaking mysterious slimy substances onto the concrete floor.

Major Adams turned to her senior enlisted soldier, as she later recalled in her autobiography. “Sergeant Major. Formation,” was all she said.

“Yes, ma’am.” The sergeant major formed up the battalion in the narrow space in front of the mountains of mail, and Adams marched to the front.

Read more: See Amazing Photos of the Real ‘Rosie the Riveter’ Women of World War II

“At ease.” The WACs relaxed their stance, hands twitching behind their backs. They stared at the mountains of mail stacked up behind their commander, 17 million pieces, they’d heard. In that moment, the stacks appeared piled up to eternity.

“I know how this looks, ladies. And I know what you’re probably thinking. But we have a job to do and we’re going to get it done. Now let’s get organized.”

She dismissed her troops and called the company leadership to her shabby makeshift office. Adams had five companies in her battalion, and she divided up the workload. Three shifts worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Under her rotation system, about 65,000 letters were processed by each shift. They got the mail moving.

Once Adams directed a system for dealing with the backlog, she turned to face the other issues. Some of the letters were addressed only to soldiers by their first name, or nickname. For example, letters could be addressed only to “Junior, U.S. Army” or “Buster, U.S. Army” with no unit noted, or just “Robby.” There were seven million Americans in Europe at the time. At least 7,500 soldiers were named Robert Smith.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

It was a mess crying out for a system to tame it. Under Adams’ direction, they set up a filing system of over seven million index cards. It was tedious, but because the battalion was also tasked with censoring troop mail being sent back to the states, it was necessary. Some packages were damaged or opened. The soldiers repacked them.

Word was spreading about what the Six Triple Eight was accomplishing.

There were a number of visitors “from HQ.” Some were curious about how the WACs were working their magic. Others wanted to express their gratitude for getting mail to their troops. Adams made certain her soldiers always looked polished and that their uniforms were “squared away” for each shift. And Adams absolutely would not stand for any racist attitudes, discrimination or attempts at segregation. She later recalled the British people were curious about them at first, but not initially friendly. “White GIs had told the locals stories about us. Tall tales. The Red Cross tried to segregate us. The British just wanted to visit us.” The white WACs used a recreational hotel in London for their leave and vacation time. They wanted a separate hotel established for the Black women. Adams just said no. The Red Cross opened a recreational club for Black women only. Her troops boycotted it. The Red Cross didn’t try again.

Many of the women found their time in Birmingham to be socially liberating. The Six Triple Eight women were often treated better by the locals than they had been at home. Many made friends and enjoyed visiting with local families. A few dated English men.

As more than seven million soldiers were finally beginning to get their delayed mail, morale was improving in units across Europe. Meanwhile, Adams endeavored to look out for her own soldiers and their needs. The Six Triple Eight was a “self-contained” unit. That meant they had everything necessary to be self-sustaining—Adams commanded the postal operations, but she was also responsible for a motor pool, a supply room, a chapel, a military police detachment, and even a battalion newsletter, Special Delivery. The Six Triple Eight built a complete community life for themselves, even hosting sports teams and sponsoring dances. Adams also made certain her soldiers had access to their very own beauty salon, a major morale booster.

Seventeen million pieces of mail later, Adams received a new set of orders. The Six Triple Eight had been so successful in England that they were ordered to undertake the same mission in France. The unit arrived at the port of Le Havre on June 9, 1945, barely a month after the end of the war, and took part in a VE day parade in nearby Rouen, marching right past the square where Joan of Arc was burned at the stake. Adams barely gave the historical marker a second glance. Joan of Arc was another woman who had stepped out of line to exert leadership and stand up for her principles. Her reward was to be reviled and executed.

That was centuries ago, Adams told herself. Her reward was the knowledge that she stood up for what she believed in and took pride in her work and her troops. She got her soldiers right to work. The mission was the same. In France, Adams’ orders were to fix a two-year backup of mail in six months. Again, the Six Triple Eight did it in three.

Experts now, they were next sent to Paris to straighten out the backlog of civilian mail there. That wasn’t a problem either. By December 1945, Adams learned she had earned another promotion, now to lieutenant colonel. When that silver oak leaf was pinned to her collar, another first, she became the highest ranking African American woman in the Army, one step below the director of the Women’s Army Corps, a full colonel. And she reached that rank in only four years. Yet another first.

By the fall of 1945, many units were packing up to go home. Some would return to their home bases; many were being disbanded. Charity Adams’ postal unit was one of those that would stand down. By March 1946, she was out of uniform, and the Six Triple Eight was deactivated.

“The women of the 6888th were under an incredible spotlight,” Beth Ann Koelsch, curator of the Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro commented. Their greatest legacy “was in changing the perception of the capabilities of women of color. Their success challenged the stereotype of African-American women.”

A bill that would award the Congressional Gold Medal to the members of the 6888th was introduced in the House this year, in recognition of their service, devotion to duty and key role in protecting troop morale in Europe. That the unit was so successful was in great part due to the leadership of their commander.

“When I talk to students they say, ‘how did it feel to know you were making history?’ But you don’t know you’re making history when it’s happening,” Adams, who would die in 2002, said during a ceremony honoring her work at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum in 1996. “I just wanted to do my job.”

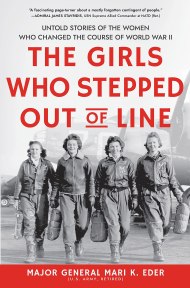

Adapted from The Girls Who Stepped Out of Line: Untold Stories of the Women Who Changed the Course of World War II by Major General Mari K. Eder, available now from Sourcebooks.

0 comments:

Post a Comment